As we navigate our daily surroundings, it’s easy to take for granted the accessibility of many of the spaces we use. While most of us largely have the benefit of feeling safe and mobile, for millions of people with disabilities, access is often difficult or impossible without proper assistance. The requirements for accessible design elements have a long history and are constantly evolving.

As architects and problem solvers, we must be knowledgeable of accessibility challenges. Our goal is to design spaces that improve the experiences of the people who use them; therefore, fully understanding accessibility standards is critical to assuring all users have pleasant and healthy experiences in the spaces where they live, work, and visit.

This is the first post in our new knowledge-sharing program known as MMA EDU. The goal is for MMA architects to educate their colleagues through a series of interactive studio presentations that address common design issues and topics we are often faced with. This blog post covers the knowledge and experiences shared by me and my colleagues, Beth Kutterer-Sanchez and Erik Piszar on the basics of accessibility and universal design.

This is the first post in our new knowledge-sharing program known as MMA EDU. The goal is for MMA architects to educate their colleagues through a series of interactive studio presentations that address common design issues and topics we are often faced with. This blog post covers the knowledge and experiences shared by me and my colleagues, Beth Kutterer-Sanchez and Erik Piszar on the basics of accessibility and universal design.

Then and Now

To understand our current standards, you must understand how we got here. The road to accessible building design has a long and storied history with many revisions and updates in guidelines and enforcement.

Early 20th century events such as the 1913 Italian Hall Disaster, which resulted in 73 people dying due to a panicked rush down a narrow staircase from a false cry of “fire,” was just one of many incidents that focused attention on the lack of safety standards. Among many others, this tragedy helped lead to the establishment of NFPA 101 Life Safety Code. Originally known as the Building Exits Code, its main purpose was focused on making factories safer for workers, and the hazards of stairways and fire escapes. Aside from making work environments safer, there was still little focus on the limitations for those with disabilities.

It wasn’t until the 1960s that we started to see a series of milestones in accessible design requirements:

American National Standard Institute (ANSI) A117.1, 1961 – ANSI was developed as a model for technical standards for accessible features, though it only acted as a guide and was unenforceable.

Fair Housing Act (FHA), 1968 – The passage of FHA made it unlawful to discriminate against those with disabilities as it related to housing.

Architecture Barriers Act (ABA), 1968 – ABA stands as the first measure by Congress to ensure access to the built environment for people with disabilities for federally-funded buildings through standards detailing design, construction, and alteration requirements. ANSI A117.1 is incorporated into these standards at this time.

Fair Housing Amendments Act (FHAA), 1988 – From 1968 to 1990, there were several revisions to these standards for specific building types, including FHAA which required adaptable features for multi-family dwellings. The Fair Housing Act was amended in 1988 to include protections for people with disabilities, requiring certain housing projects to meet a basic level of accessibility.

Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA), 1990 – After years of advocacy from disability rights organizations and other concerned citizens, President George H.W. Bush signed into law ADA, which becomes the most comprehensive civil rights protection for people with disabilities. It established design requirements for the construction or modification of facilities required to be accessible. It covers facilities in the private sector (places of public accommodation and commercial facilities) and the public sector (state and local government facilities).

ADA Standards for Accessible Design (ADAAG), 1991 – Adopted by the US Department of Justice, which formally provided technical requirements implementing ADA.

Tragic events followed by decades of activism led to the passing of ADA in 1990 by President George H. W. Bush. (Photo Credit: Disability History Museum)

From 1991 through today, the ADA was revised several times to include more stringent standards for specific spaces, including transportation facilities, defense facilities, and outdoor developed areas on federal lands. In 2014, the ADA and ABA Accessibility Guidelines for Buildings and Facilities were updated and it’s the current version we use still today.

Learn more about these milestones

Beginning the process

Understanding the challenges of each project early is key to successful integration of accessible design. Many different building elements and goals can conflict with accessibility requirements such as sustainability, historic preservation, safety and security, and location. Identifying these in collaboration with all stakeholders can help the entire team avoid potential problems and assure a successful project that meets the necessary standards.

For example, Mackey Mitchell worked closely with key stakeholders and several representatives with different types of disabilities, including the deaf, the blind and wheelchair-bound people, in the early stages of planning for the renovation of our Soldiers Memorial Military Museum project. Getting feedback from the users of the building was critical to gaining a full understanding of their needs and to assure accessibility for all veterans, their families and any visitor to the museum regardless of disability.

To accessibility and beyond!

The standards covered here, such as ABA and ADA, establish minimum requirements that protect people with disabilities from discrimination in the built environment. However, our goal is always to design at the broadest level for diversity and equity. Universal design, the term for this revised approach, was based on the idea that the environment should be much more accessible than the minimum requirements of the law.

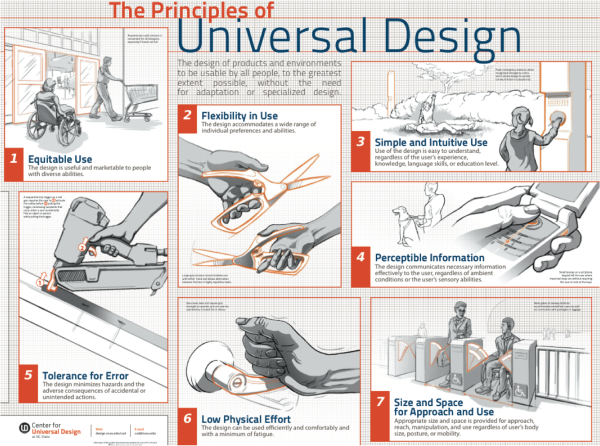

“The design of products and environments to be usable by all people, to the greatest extent possible, without the need for adaptation or specialized design.” —Center for Universal Design

The Center for Universal Design at NC State University collaborated with industry professionals to establish the Principles of Universal Design that can be applied to evaluate existing designs and guide the design process to create more usable products and environments. These Principles were a valuable tool for clarifying universal design for early adopters, and are still widely used today:

- Equitable Use – The design is useful and marketable to people with diverse abilities.

- Flexibility in Use – The design accommodates a wide range of individual preferences and abilities.

- Simple and Intuitive Use – Use of the design is easy to understand, regardless of the user’s experience, knowledge, language skills, or current concentration level.

- Perceptible Information – The design communicates necessary information effectively to the user, regardless of ambient conditions or the user’s sensory abilities.

- Tolerance for Error – The design minimizes hazards and the adverse consequences of accidental or unintended actions.

- Low Physical Effort – The design can be used efficiently and comfortably and with a minimum of fatigue.

- Size and Space for Approach and Use – Appropriate size and space is provided for approach, reach, manipulation, and use regardless of user’s body size, posture, or mobility.[1]

Each principle above is succinctly defined and contains a few brief guidelines that can be applied to design processes in any realm: physical or digital (see infographic below). These principles are broader than those of accessible design and barrier-free design and strive to make life easier and healthier for all.

(click to expand)

Universal Design in Practice: Soldiers Memorial Military Museum

Mackey Mitchell incorporated several Universal Design Principles into the renovation of Soldiers Memorial Military Museum. The following are examples of a few of those features, which are numbered in correlation to the principles above.

In the last ten years, we have seen a broader emphasis on designing for other types of social inclusion. A newer definition is more relevant to all citizens without ignoring people with disabilities. While these universal design principles are increasingly being incorporated into building design and construction, we must continue improving them and strive to ensure wellness and accessibility for all.

[1] https://projects.ncsu.edu/design/cud/about_ud/udprinciples.htm

By: Erik Biggs

By: Erik Biggs