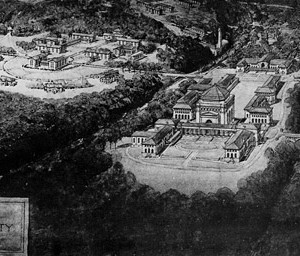

In 2014, Mackey Mitchell was invited to participate in a design competition for Emory University’s Center for Campus Life. In our visits to campus, we enjoyed exploring the work of Henry Hornbostel (1867-1961), architect of the the original student union and several other buildings on the Emory campus.

Throughout his career, Hornbostel possessed a rare gift for turning the everyday, ordinary project into something really special. His work at Emory University is a perfect demonstration of this prowess. He was initially commissioned to provide a campus master plan for Emory’s new Atlanta campus, an endeavor made possible through the generosity of Asser Candler, then CEO of the Coca Cola Company. The resulting plan fit the campus seamlessly with the area’s undulating terrain.

As “iridescent opals deep in a green jewel casket,” the architecture of Emory University is well known for being dressed in that most sumptuous of materials, pink and grey Georgia marble. How did that come to be? With limited means, Hornbostel sought every opportunity to render maximum service and that began with studying the available local materials. In Atlanta, Hornbostel visited the surrounding quarries taking note of the large amount of waste material, the first sawing of the rough blocks quarried from the earth. The cast off material had one plane face, the back being uneven and thickness varying from one to several inches.

Using this waste material was a design problem in the highest order. Hornbostel determined the slab should be roughly cut into square and rectangular forms, the faces polished, and edges made square and true. The offal’s color range embraced almost every shade of gray, pink and brown. The pieces were placed in the wall randomly without reference to size or color with few exceptions. The walls of the early Hornbostel buildings are cast in place concrete. The marble facing was cast directly into the walls against the formwork’s exterior face, solving the issue of the variable material depth. The marble pieces were placed and joints closed with a sparse amount of plaster of Paris – remarkable in that there are no apparent mortar joints. Wire anchors tie the marble back into the poured concrete.

Michael C. Carlos Hall, Lamar School of Law (Photo Credit: Robert M. Craig, Society for Architectural Historians)

Cast as veneer, the apparent absence of mortar joints gives the marble surface a modern effect, its beauty all the more remarkable when you realize it was not laid out by any drawing but determined in the field, during construction – an unordered arrangement in size and color provides the surface its great beauty and charm.

Working with what would otherwise be waste material, Hornbostel achieved the extraordinary. How can we, as designers, use a similar strategy for accomplishing the exceptional with modest resources. Imagine incorporating the use of locally quarried cast off material into modern, insulated precast concrete wall panels. Could the promise of offsite precision and speed keep pace with what Hornbostel was able to achieve nearly 100 years ago? How tight could you make the seam between the panels? Could the panels withstand the stress and potential damage of transportation? The University of Missouri Kansas City’s new Bloch Center employs just such an approach casting terra cotta tiles reflecting the surrounding campus character. The inside face of the wall is sandblasted as a finished wall surface.

UMKC Bloch School of Business, Designed by BNIM Architects with MRY Architects. Photo Credit to Enterprise PreCast

The grouping of buildings and surrounding relationship with topography and woods makes Emory one of North America’s greatest campuses. The contributions Hornbostel made from master plan vision down to the intimate constructability, are timeless and indelible – “great credit is due to that master mind and skilled hand which has found a use for a waste product – a use that has resulted in buildings of incomparable beauty. It requires a certain measure of bravery on the part of the architect to make such a radical departure from the traditional methods and design applied to such an important project.”

The late, great American architect, Michael Graves, who designed the 1983 expansion to the original Hornbostel building, Michael C. Carlos Museum, said, “Seeing these buildings of Hornbostel’s was an extraordinary experience and something I’ll never forget because immediately it struck me that whoever this was, as I didn’t even know at the time, the architect knew how to do that very precious kind of college building. That these buildings of learning had the right amount of connectivity to each other and somehow the right amount of transparency with the campus. He simply loved making buildings. I would have loved to talk to him.”

Looking to feed and energize your own creative grist mill? When designing for a beloved organization like a college campus, start with boundless curiosity for everything there is to know about the institution. Broaden your perspective by learning about how the institution came to be. Curate an historian’s knowledge of the backdrops of alumni’s cherished memories. Be a student of the source code for the campus guiding spirit, promise, purpose and sense of place. In being curious about the past, present, and future, you will always have an endless source for inspiration.

Author John Burse is a nationally-recognized expert as well as an award-winning designer of student unions and student centers across the country. You can learn more about him HERE as well as see our student center work HERE.

By: John Burse

By: John Burse