Keeping water out of buildings – it is a problem humans have grappled with since constructing the earliest shelters.

As buildings got increasingly more complex, craftsmen, builders, and eventually architects, specialized in solving this problem. Throughout history new advancements in building technology have required new techniques for keeping building interiors dry.

Renovation projects offer critical opportunities to reconcile construction methods of the past with current approaches and sophisticated systems, particularly when portions of the original construction are to remain in place.

The design-build team of Clayco/DLA+ Architecture & Interior Design and Mackey Mitchell Architects is currently implementing a dramatic revitalization of the East Halls residences at The Pennsylvania State University – home to nearly 4900 freshman students at the University Park campus. This ambitious multi-year, multi-phased project involves extensive renovations of 14 residence halls, the addition of two new halls and extensive site enhancements. The existing buildings – over fifty years old – required wholesale systems replacement and programmatic upgrades to meet the needs of today’s students.

In establishing the construction budget, Penn State prioritized interior upgrades since those were the areas where students would experience the greatest benefit. Through creative planning with Penn State physical plant and housing staff, our D-B team conceived of exterior improvements to address rehabilitation needs, as well as aesthetic enhancements. While these alterations to the building exteriors far exceeded client expectations, the budget did not support total façade removal and replacement.

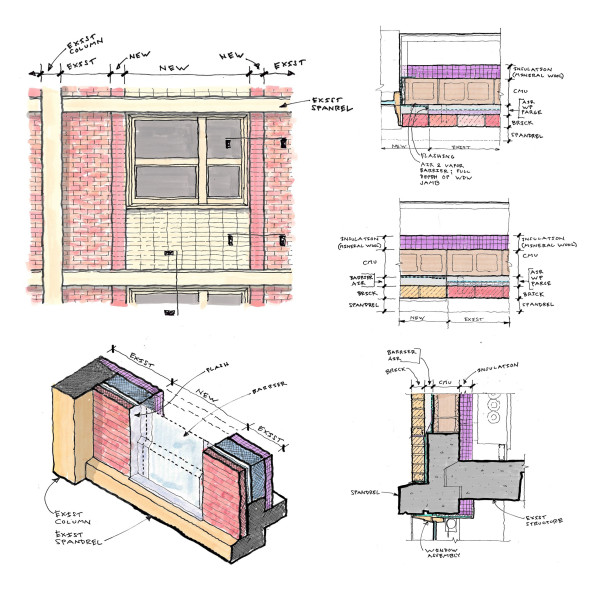

Because significant portions of the existing cladding were to remain, the primary challenge was to successfully marry new cladding with existing, without compromising water tightness. This was even trickier because of the unique method used for keeping the water out 50 years ago compared to today. On East Halls, a barrier system was used, while today we most commonly use a rainscreen system for exterior masonry walls.

The existing exterior wall construction at East Halls typically consists of brick veneer with concrete masonry unit (CMU) back-up set within a concrete structural frame. The barrier waterproofing system was achieved by applying a cementitious parge coat (about ½” to ¾” thick) on the cavity side of the exterior brick veneer. Once this brick veneer wall was set, a bituminous coating was applied over the entire area of the cement layer. Then the CMU back-up was laid and tied to the brick veneer with galvanized reinforcing. For anyone who has watched a mason work, this method must have been an arduous feat of craftsmanship! Much to the team’s surprise, upon field investigations of the façades at East Halls, the buildings that employed the barrier system outperformed buildings that didn’t employ a waterproofing strategy. Because of this, the existing façade only needed minor repairs.

In contrast, the rainscreen system locates the weather barrier on the surface of the CMU back-up wall. In this manner, the brick can breathe, flashing and weeps direct the water out of the cavity and ventilation at the top of the cavity keeps air circulating. The brick veneer also provides a bit of added protection for the waterproofing within the cavity. This method represents the latest in current masonry cavity wall design.

The most pressing challenge facing our team was how to effectively bridge the two very different methods to achieve a seamless water-tight envelope. As a result, through careful coordination and team problem solving among key designers and builders on our team, a solution for effectively bridging the transition between existing barrier system and new rainscreen system was devised. It included vertical metal flashing installed between the existing masonry and areas where new brick veneer was to be added. Backer rod and sealant between the metal flashing and brick will maintain air and water tightness. This separation will allow for a new fluid-applied weather barrier to be used and applied to the face of the CMU backup, rather than the back of the brick as before, and allow proper drainage and ventilation (see diagrams).

Learning about the barrier method used at East Halls has been a fascinating bit of archaeology that has expanded our appreciation of the craftsmen who came before us.

By: Chris Harpstrite

By: Chris Harpstrite